ᖄᓇ ᑐᒃᑐ | Hannah Tooktoo

ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᑐᓴᐅᒪᓲᑦ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᓗᐊᕐᐸᓂᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᓄᓇᓕᑐᖃᑦᓴᔦᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᖏᓐᓂ; ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐊᒥᓱᑦ ᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᑐᕕᓂᐅᖕᖏᑐᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᒐᓛᖕᖏᑐᑦ ᐊᑑᑎᓪᓚᕆᑉᐸᑕᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᔨᐊᓖᑦ ᐃᓚᒋᔦᑦ, ᐃᓚᓐᓈᕆᔦᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᒥᐅᖃᑎᒌᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᑐᕕᓃᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᖏᓐᓂ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕐᓂᖅ ᐅᓪᓗᑕᒫᑐᐃᓐᓇᐅᔮᓕᕐᑎᓗᒍ. ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ ᓄᓇᓕᓐᓂ ᑰᑦᔪᐊᖅ ᐊᖏᓂᕐᐹᖅ ᐃᓄᖃᕐᓱᓂ 2500 ᓴᓂᐊᓃᑦᑐᓂᒃ. ᐊᐅᐸᓗᒃ 14-ᓂ ᓄᓇᓕᓐᓂ ᒥᑭᓂᕐᐸᐅᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᐃᓄᖏᑦ 200 ᐅᖓᑖᓄᐊᐱᑐᐃᓐᓈᓱᑎᒃ. ᐃᓘᓐᓇᑎᒃ ᓄᓇᓖᑦ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᐅᑎᑦᓯᐊᑐᑦ ᐃᓚᒥᑎᒍᑦ, ᓄᓇᓕᒥᐅᒍᖃᑎᒌᖕᖏᑐᑦ ᑲᑎᑎᑕᐅᕙᓐᓂᖏᑎᒍᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓚᓐᓈᕇᓐᓂᑎᒍᑦ. ᓄᓇᓖᑦ ᐅᖓᓯᑦᑕᕇᓈᕐᑎᑑᒐᓗᐊᑦ ᐊᖏᔪᒥᒃ ᓄᓇᕐᓚᒥ, ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐃᓅᖃᑎᒌᑦᓯᐊᑐᑦ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᐅᑎᑦᓯᐊᓱᑎᒃ ᓄᓇᓕᓕᒫᓂ. ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᔨᐊᖃᕐᑐᖃᕐᒪᑦ, ᓄᓇᓖᑦ ᓇᓪᓕᖏᓪᓘᓃᑦ ᐊᑦᑐᑕᐅᒻᒣᑑᓲᒍᑦᔭᖏᑦᑐᑦ. ᓄᓇᓕᓐᓂ ᑎᒦᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐋᓐᓂᐊᕖᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐋᓐᓂᐊᓯᐅᑎᒃᑯᑦ ᑲᔪᓯᑎᑦᓯᒐᓱᐊᕐᐸᑐᑦ ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕋᑦᓴᓂᒃ ᒪᒥᓴᕐᓂᒥᒃ ᑫᓪᓗᑐᐃᒐᓱᐊᕈᑎᒋᑦᓱᒋᑦ. ᐊᒥᓲᒐᓗᐊᑦ ᐃᓄᑦᓯᐊ ᑖᒃᑯᓇᓂ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕐᓂᒥᒃ ᓄᕐᖃᑎᑦᓯᒐᓱᐊᕐᐸᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓗᓯᕐᓱᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐱᕙᓪᓖᒋᐊᕋᓱᐊᕐᐸᓱᑎᒃ, ᓱᓕ ᐋᕐᖀᒋᐊᕈᑎᑦᓴᒋᐊᓪᓓᑦ ᑭᖕᖒᒪᓇᕐᐳᑦ. ᑕᒪᒃᑯᐊᓗ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᖁᑎᒋᒐᔭᕐᑕᖏᑦ ᐅᓂᑦᓯᒪᐅᑎᖃᓪᓚᕆᑦᑐᑦ, ᐱᓇᓱᑦᑎᖃᑦᓯᐊᖏᓐᓂᒥᒃ ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕈᑎᑦᓴᖃᑦᓯᐊᖏᓐᓂᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑭᒡᒐᑐᕈᑎᓂᒃ ᐃᑲᔫᑎᑦᓴᓂᒃ ᑲᒪᒋᐊᖃᕐᑐᖃᓕᕐᐸᑦ ᐅᒡᒍᐊᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓗᓯᕐᓱᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᑕᕐᕋᒥ. ᕼᐋᓇ ᑐᑦᑐ ᑌᒫᒃ ᐃᓱᒪᒋᔭᖃᕐᐸᓕᐊᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᖃᐅᔨᓕᓂᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᓄᓇᓕᒥᓂ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕐᑐᖃᕐᐸᑎᓪᓗᒍ ᐊᕐᕌᒍᓂ ᐊᒥᓱᓂ ᐊᓂᒍᕐᓯᒪᓕᕐᑐᓂ. ᕼᐋᓇ ᑐᑭᑖᕐᑐᕕᓂᖅ ᐯᓰᑰᓛᕆᐊᒥᒃ ᕚᓐᑰᕙᒥᑦ ᐱᓗᓂ ᒪᓐᑐᔨᐊᓪ ᑎᑭᓪᓗᒍ ᐊᐅᔭᖅ, ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᓕᕐᑎᓯᒋᐊᕐᓗᓂ ᓴᐳᑦᔭᐅᓯᐊᖕᖏᓂᕐᒥᒃ, ᑭᒡᒐᑐᕐᕕᖃᑦᓯᐊᖏᓐᓂᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᓇᓱᑦᑎᖃᑦᓯᐊᖏᓐᓂᓂᒃ ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕈᑎᑦᓴᖃᑦᓯᐊᖏᓐᓂᓂᒃ ᓄᓇᒥᓂ ᓇᓂᓕᒫᖅ.

ᐱᒋᐊᕐᕕᖃᕈᒪᔪᖅ ᐳᔨᑎᔅ ᑲᓛᒻᐱᐊ ᖃᕐᖄᓗᖏᓐᓂᑦ ᑐᑭᖃᕐᑎᓯᓗᓂ ᒪᒥᓴᕐᓂᐅᑉ ᐱᒋᐊᕐᓂᖓ ᐱᔭᕆᐊᑐᓂᕐᐸᐅᓲᒍᒻᒪᑦ. “ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔪᖓ ᓄᓇ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑎᒥᐅᑉ ᐊᐅᓚᓂᖓ ᐋᓐᓂᐊᓯᐅᑎᐅᒋᐊᖏᒃ. ᐯᓯᑰᕐᑎᓚᐅᖕᖏᑐᖓ. ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔪᖓ ᐱᒐᓱᐊᒻᒪᕆᓛᕆᐊᒥᒃ, ᐱᓗᐊᕐᑐᒥᒃ ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕈᓰᓐᓂ ᒪᕐᕉᓂ, ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐱᒐᓱᐊᒻᒪᕆᓐᓇᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᓂᒍᐃᑦᓯᐊᓛᕈᒪᔪᖓ. ᐃᓱᒪᑎᒍᑦ ᐃᓗᓯᕐᓱᓚᖀᒍᑎᑦᓴᓂᒃ ᑕᒪᓐᓇ ᐋᕐᕿᓚᕿᓗᒍ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᕋᖕᖏᑐᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᕐᖃᑎᑦᓯᒍᓐᓇᓛᕆᐊᒥᒃ ᐃᓅᖃᑎᑦᑎᓂᒃ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕈᒪᕙᑦᑐᓂᒃ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᖕᖏᓚᖀᓛᕐᑐᖔᓚᓇᖓ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᕋ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᐊᐱᒻᒥᐅᓃᑦ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᖕᖏᓚᖀᑉᐸᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗᐊᓪᓛᑦ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᒃ ᑌᒫᒃ ᐃᓱᒪᒍᓐᓀᑎᒍᒪ, ᐊᓕᐊᓛᕐᑐᖓ”.

ᑖᓐᓇ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᕆᓛᕐᑕᕋ ᐃᓕᖓᔪᖅ ᓇᒻᒥᓂᖅ ᒪᒥᓴᕐᓂᓄᑦ: “ᓄᓇᕐᓚᒧᑦ ᐃᓕᓴᕆᐊᓚᐅᕐᓯᒪᑦᓱᖓ ᑌᒪᖕᖓᑦ ᑭᑦᓴᐸᑦᑐᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓪᓚᖓᕐᖃᔭᕐᓇᖓ, ᓄᓇᕐᓚᒨᕐᖃᒥᐅᑦᓱᖓ ᐃᓗᒡᒍᓯᑦᑕ ᐊᑦᔨᒋᖕᖏᑕᖓᓅᑲᓪᓚᓱᖓ ᖁᐊᕐᓵᖓᓯᒪᔪᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓇᕐᕋᕈᒪᓪᓕᓱᖓ. ᖃᓪᓗᓈᑦ ᓄᓇᖓᓃᑦᓱᖓ ᑐᓴᕐᓱᖓ ᐃᓚᓐᓈᓃᕙᖓ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕐᑐᕕᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᒥᐅᒍᖃᑎᒃᑲ ᐃᓕᐊᕐᕆᒍᑎᖃᕆᐊᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕐᓱᑎᒃ ᐃᓅᒍᓐᓀᓚᕿᔪᓂᒃ ᑖᕐᓂᓴᒨᕈᑎᖃᕐᓯᒪᔪᖓ ᐊᓕᐊᓇᖕᖏᑐᓪᓚᕆᒻᒧᑦ. ᖃᐅᔨᒪᑦᓱᖓ ᐋᓐᓂᐊᕈᑎᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᕿᒣᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᐋᓐᓂᐊᓂᐊᓗᒻᒥᓂᒃ, ᐅᖓᓯᑦᑐᒦᒐᒪ ᐃᑲᔪᕐᑎᓴᖃᖕᖏᓚᕆᓐᓂᒥᒃ ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᖃᑦᑕᓯᒪᑦᓱᖓ. ᐃᓚᒃᑲᓗ ᐃᓚᓐᓈᑲᓗ ᑲᑎᒪᓇᒋᑦ ᓭᒻᒪᓭᔨᑦᓴᑲ. ᑎᑭᐅᑎᓂᖃᓚᐅᔪᔪᖓ ᑭᑦᓴᓂᕐᒧᑦ ᓄᓪᓚᖓᕐᖃᔦᕐᓯᒪᓂᕐᒧᓗ. ᐅᓪᓗᐃᑦ ᐃᓚᖏᓐᓂ, ᓯᓂᕝᕕᓃᕙᖓ ᒪᑭᒍᓐᓇᖏᕐᓯᒪᖃᑦᑕᓚᐅᔪᔪᖓ. ᐃᓱᒪᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓗᓯᕐᓱᖏᓐᓂᕋ ᑎᒥᓐᓃᕙᖓ ᓱᒃᑯᑎᑦᓯᓯᒪᓚᐅᔫᖅ. ᐅᓐᓄᐊᒥ ᓯᓂᕐᖃᔭᕐᓇᖓ, ᖁᐃᑦᑎᓱᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑎᒥᓐᓃᕙᖓ ᑲᒪᑦᓯᐊᕈᒣᕐᓱᖓ. ᑕᒉᓐᓇᓗ ᓱᓇᐅᓪᓗᐊᖏᑦᑑᒐᓗᐊᓂᒃ ᓴᐱᕈᑎᖃᑦᓴᐅᑎᒋᕙᓕᕐᓱᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓱᒪᒃᑯᑦ ᑕᖃᓪᓚᕆᑦᓱᖓ, ᓂᖕᖓᕈᐊᕐᑑᓕᕐᓱᖓ ᕿᑐᕐᖓᓃᕙᖓ ᑲᒪᑦᓯᐊᕈᓐᓇᖏᕐᓱᖓ ᐁᑉᐸᓃᕙᖓᓘᓐᓃᑦ. ᐃᖏᕐᕋᕈᑎᖃᕐᓗᖓ, ᑕᑯᒍᓐᓇᓯᓛᕈᒪᔪᖓ ᐊᑦᑕᓀᑦᑐᒦᒍᓐᓀᕈᑎᑦᓴᒥᒃ, ᒪᒥᓴᕈᑎᒋᓗᒍᓗ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓕᐊᓇᕐᑐᓂᒃ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᓂᕆᐅᒍᓐᓇᓯᒍᑎᒋᓗᒍ. ᕿᑐᕐᖓᓃᕙᖓ ᑲᒪᑦᓯᐊᓂᕐᓴᐅᓛᕈᒪᓕᕐᑐᖓ, ᐁᑉᐸᓃᕙᖓᓗ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᖕᖑᓯᐊᕆᐊᓪᓚᓗᖓ. ᕿᒣᓛᕈᒪᔪᖓ ᓱᒃᑯᓇᕐᑐᓕᒫᓂᒃ ᐋᕐᕿᒍᑎᒋᒐᓱᐊᖃᑦᑕᓚᐅᔪᔮᕐᓃᕙᖓ ᐅᕙᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᑲᔪᕐᓯᒪᕐᖃᔭᕈᓐᓀᑐᓂᒃ.” ᐱᒐᓱᐊᒻᒪᕆᐅᑎᒥᓂᒃ ᑐᓴᕐᑎᓯᖃᑦᑕᓛᕈᒪᔪᖅ Facebook-ᑯᑦ ᐊᑎᖃᕐᑎᓗᒍ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᕕᖓ ᕼᐋᓇᐅᑉ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᖓ ᑳᓇᑕᓕᒫᒥ: “ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᖃᑦᑕᓗᖓ ᓱᓇᑎᒎᓕᕐᓂᓃᕙᖓ, ᑭᓇᑐᐃᓐᓇᒥᒃ ᓲᖑᓯᑎᑦᓯᒍᓐᓇᓯᓛᕈᒪᕗᖓ ᐃᓗᒥᓂᑦ ᐱᔪᓂᒃ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐅᓄᕐᓂᓭᑦ ᐃᑉᐱᒍᓱᒍᓐᓇᓯᑎᓗᒋᑦ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᑐᕕᓃᑦ ᓄᓇᓕᖏᑦᑕ ᐱᓀᓗᑕᕐᓂᒃ ᓵᖕᖓᒋᐊᖃᕐᐸᑕᖏᓐᓂᒃ.”

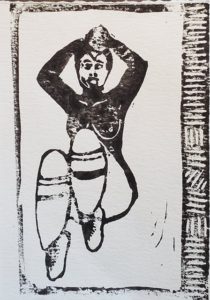

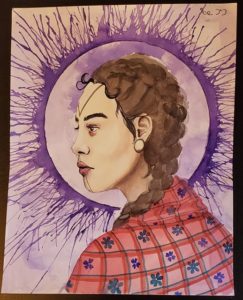

ᕼᐋᓇ ᐊᕐᕌᓂ ᐱᔭᕇᓚᐅᔫᖅ ᐃᓕᓴᕐᓂᒥᓂᒃ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ ᓯᕗᓂᑦᓴᕗᑦ ᐃᓕᓐᓂᐊᑎᑦᓯᒍᑎᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᓪᓗᒥ ᐃᓕᓴᓕᕐᓱᓂ ᑕᑯᒥᓇᕐᑐᓕᕆᓂᕐᒥᒃ Dawson College-ᒥ. ᑕᑯᓐᓇᕋᑦᓴᖁᑎᓕᒃ ᐅᖃᐅᑦᔪᐃᒍᑎᒥᒃ ᐊᑎᖃᕐᑎᓗᒍ “ᐃᒻᒥᓂᐊᕐᓂᖅ” ᓇᒧᓕᒫᖅ ᐃᕐᐸᓯᒪᓕᕐᑐᒥᒃ, ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑕᐅᒋᐊᓪᓚᓯᒪᑦᓱᓂᓗ 600 ᐅᖓᑖᓄᑦ facebook-ᑯᑦ. ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᓕᒫᒥᓂ, ᕼᐋᓇ ᒥᖑᐊᕐᓯᒪᔪᓕᐅᖕᖑᐊᖃᑦᑕᓛᕈᒪᔪᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕐᓂᓗ ᑐᓴᕐᓂᑐᓕᐅᖃᑦᑕᓗᓂ. ᓲᖑᓯᑎᑦᓯᒋᐊᕈᒪᔪᖅ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑐᑦ ᐱᔪᓐᓇᓯᐊᕈᑎᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᕆᑕᐅᔭᒃᑯᑦ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᒐᓱᐊᖃᑦᑕᓛᕐᓱᓂ ᑕᑯᑦᓴᐅᑎᑦᓯᕕᒻᒥᓂ ᕼᐋᓇᐅᑉ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓂᖓ ᑳᓇᑕᓕᒫᒥ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑑᕐᑎᓗᒋᑦ. Dawson-ᒥ ᐱᔭᕇᕐᒥᒍᓂ, ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒧᑦ ᓅᒋᐊᓪᓚᓛᕈᒪᔪᖅ ᐃᓚᒥᓃᒋᐊᓪᓚᕆᐊᕐᑐᓗᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᕐᒥᓂᒃ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑐᑦ ᐃᓕᑦᓯᑲᓂᕆᐊᕐᓗᓂ. ᐸᕐᓀᓯᒪᑦᓱᓂᓗ ᐊᓈᓇᒥᑕ ᑰᑦᔪᐊᕌᐱᒻᒥᐅᑎᑐᑦ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᖓᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᕈᓐᓇᓯᑦᓯᐊᕆᐊᓛᕐᓱᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐸᓂᒻᒥᓂᒃ ᑌᒫᑦᓭᓇᖅ ᐃᓕᑦᓯᒋᐊᖃᕐᓂᖓᓂᒃ ᑲᒪᒋᐊᓯᓗᓂ.

Plusieurs personnes ont entendu parler des articles et des statistiques sur l’épidémie de suicide parmi les communautés autochtones et inuites, mais cela est bien différent que de réellement vivre la perte des membres de sa famille, amis et membres de la communauté. Au Nunavik, la communauté la plus peuplée, Kuujjuaq, compte environ 2 000 habitants. La plus petite, Aupaluk, compte à peine 200 citoyens. Lorsqu’il y a un suicide, la nouvelle se passe assez vite au Nunavik. Il y a très peu de ressources pour la santé mentale, les expériences post-traumatiques et la guérison suite à la violence. Et lorsque les suicides surviennent par vagues celles-ci sont encre plus limitées. C’est la raison pour laquelle Hannah Tooktoo, pour sensibiliser la population à cet enjeu, a décidé cet été de faire du vélo de Vancouver à Montréal.

Elle dit que ce voyage a pour but de guérir: « Après avoir subi tant de pertes reliées au suicide, je suis devenue déprimée, je ne voulais pas quitter mon lit, je mangeais mes émotions. Ma santé mentale affectait ma santé physique. C’était aussi lié au choc culturel de commencer à vivre à Montréal. Je veux retrouver cette Hannah de Kuujjuaq qui était une meilleure version de moi-même. Je veux être une meilleure mère, une meilleure épouse pour mon mari et un meilleur moi-même. “

Elle débute son voyage dans les montagnes de Colombie-Britannique, une métaphore du fait que la partie la plus difficile de la guérison est le début. «Je ne suis pas une spécialiste pour dire que faire du vélo à travers le Canada est la solution à ce problème, mais si cela peut aider au moins une personne et que même cette personne est moi, je serai heureuse».

Hannah a obtenu son diplôme l’an dernier au programme Nunavik Sivutnisavut et étudie actuellement les arts visuels au collège Dawson. Sa vidéo de poésie nommée « Suicide » est devenue virale et partagée plus de 600 fois sur Facebook. Tout au long de son parcours, Hannah a déclaré qu’elle aimerait peindre et écrire de la poésie après ses journées de vélo. Elle utilise plus souvent l’anglais, mais elle souhaite utiliser davantage d’inuktitut et va avoir un journal de voyage qu’elle traduira en inuktitut et partagera sur les réseaux sociaux. Lorsqu’elle aura terminé ses études, elle souhaite vivre dans différentes communautés pour créer des liens avec les membres de sa famille et parler l’inuktitut comme elle est habituée et apprendre les dialectes.

People hear about the statistic about the suicide epidemic among Indigenous and Inuit communities; but most non-indigenous people cannot imagine the actual experience of losing relatives, friends and community members at the high rates that is occurring in Inuit and Indigenous communities. The biggest community in Nunavik is Kuujjuaq with a population of approximately 2700. Aupaluk is the smallest of the fourteen communities with a population of just over 200. All communities within Nunavik are interconnected through family, marriage and friendship. Although the communities are spaced out over a vast land, the Inuit interrelation connections make the people of the region close knit. When loosing someone to suicide, there is no community that does not feel the ripples of grief. Local organisations and the hospitals and clinics try to implement mental health awareness and activities; using workshops, sports and on-the-land activities to encourage healing. Although there are many good people out there trying to combat the suicide epidemic and promote mental health, there is still room for improvement. When it comes down to it, there is not enough resources and services to lean on when dealing with grief and mental health in the north. That is the realisation Hannah Tooktoo came to after watching her community, Kuujjuaq, deal with suicide over the years. Hannah decided that she will bike from Vancouver to Montréal this summer, to bring awareness of the lack of support, services and resources in her region.

She wants to start from the mountains in British Columbia as a metaphor that the beginning of a healing journey is the toughest part. “I know that nature and moving your body is medicine. I am not a professional cyclist. I know that I will have a hard time, especially in the first two weeks, but I hope to push past the hardship. I do not claim to know how to fix our mental health and stop my Inuuqatiks (companions or neighbours) from committing suicide but if the journey can help at least one person and even this person is me, I will be happy”.

This trip is about healing herself: “I have been dealing with depression and anxiety since I moved to the city for school, where I dealt with culture shock and homesickness. Living in the South and hearing about my friends and community members suffering and dying from suicide plunged me into a darker place. Knowing how much pain they had dealt with and all the pain they left behind, I felt helpless living so far away. I also had none of my family members and friends to lean on. I came to the point where my depression and anxiety took over. Some days, I was not able to leave my bed. My mental health was affecting my physical health. I can’t sleep at night, I gained weight and lost all interest in taking care of my body. I was easily overwhelmed and mentally exhausted, leading me to be short tempered and not the best mother or partner. Through this journey, I hope to find stability, and healing and be positive. I want to be a better mother, a better partner for my husband and a better self. I want to unlearn all the toxic coping mechanisms that do not help me anymore.” She wants to share her struggles on her Facebook page Hannah’s Journey Across Canada: “I hope that by sharing what I am going through, that someone out there will find strength within themselves, and that more people will be aware of the issues Inuit and Indigenous communities face.”

Hannah graduated last year at the Nunavik Sivunitsavut program and is currently studying Visual Arts at Dawson College. She has a video of spoken words entitled “Suicide” which went viral, getting shared over 600 times on Facebook. Across her journey, Hannah would love to paint and write poetry. She wants to strengthen her Inuttitut skills and will be making an effort to post on her page Hannah’s Journey Across Canada in Inuttitut. Once she graduates from Dawson, she wants to move back to Nunavik to bond with her family members and regain fluency in Inuttitut. She also plans to learn her mother’s Kuujjuarapik dialect and ensure her daughter learn as well.

ᕼᐋᓇ ᐃᖏᕐᕋᓕᕐᐸᑦ ᐯᓯᑰᕐᓗᓂ ᑕᑯᒐᓱᐊᖃᑦᑕᓛᕐᙯᑦ | Pour suivre Hannah durant son séjour | Follow Hannah in her journey: Hannah’s Journey Across Canada

ᕼᐋᓇᒥᒃ ᓴᐳᑦᔨᓂᖃᕆᐊᕐᓗᑎᑦ | Pour aider Hannah | To Support Hannah: GoFund Me

ᐊᓪᓚᑐᖅ | Texte de | Text by: Olivia Lya Thomassie