ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒃ ᐋᑦᑕᓯ ᓇᑉᐹᓗᒃ, 1931-2007 | Mitiarjuk Attasie Nappaaluk, 1931-2007

ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒃ ᐋᑦᑕᓯ ᓇᑉᐹᓗᒃ, ᑲᖏᕐᓱᔪᐊᕐᒥᐅᕕᓂᖅ, ᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᕐᔪᐊᖃᕐᓯᒪᔪᖅ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᔪᑦᓴᐅᔮᕐᓱᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᓕᐊᒋᔭᖃᒻᒪᕆᑦᓱᓂ ᐃᓗᒡᒍᓯᒥᓂᒃ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᑕᐅᑎᑦᓯᒍᒪᓪᓚᕆᑦᓯᒪᑦᓱᓂ ᐃᓕᓭᒍᑎᒋᓗᒍ. ᐃᓅᒍᓐᓀᑐᕕᓂᒃ 2007-ᒥ, ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒃ ᕿᒣᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᑦᔨᒌᖕᖏᑐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᐅᓚᔨᔭᒥᓂᒃ ᕿᑐᕐᖓᕇᓕᒫᓄᑦ ᑖᕗᖓᓕᒫᖅ ᖃᐅᔨᔭᐅᒍᓐᓇᓯᑎᑦᓯᒋᑦ. 1965-ᒥ ᑎᑭᑦᓱᒍ 1996, ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕐᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᑲᑎᕕᒃ ᐃᓕᓴᕐᓂᓕᕆᓂᕐᒥ ᑐᑭᓯᓂᐊᕐᕕᐅᓱᓂ, ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑐᑦ ᐃᓕᓭᔨᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓗᒡᒍᓯᒥᒃ ᓄᓇᕕᒻᒥ ᐃᓕᓴᕐᕕᓂ.

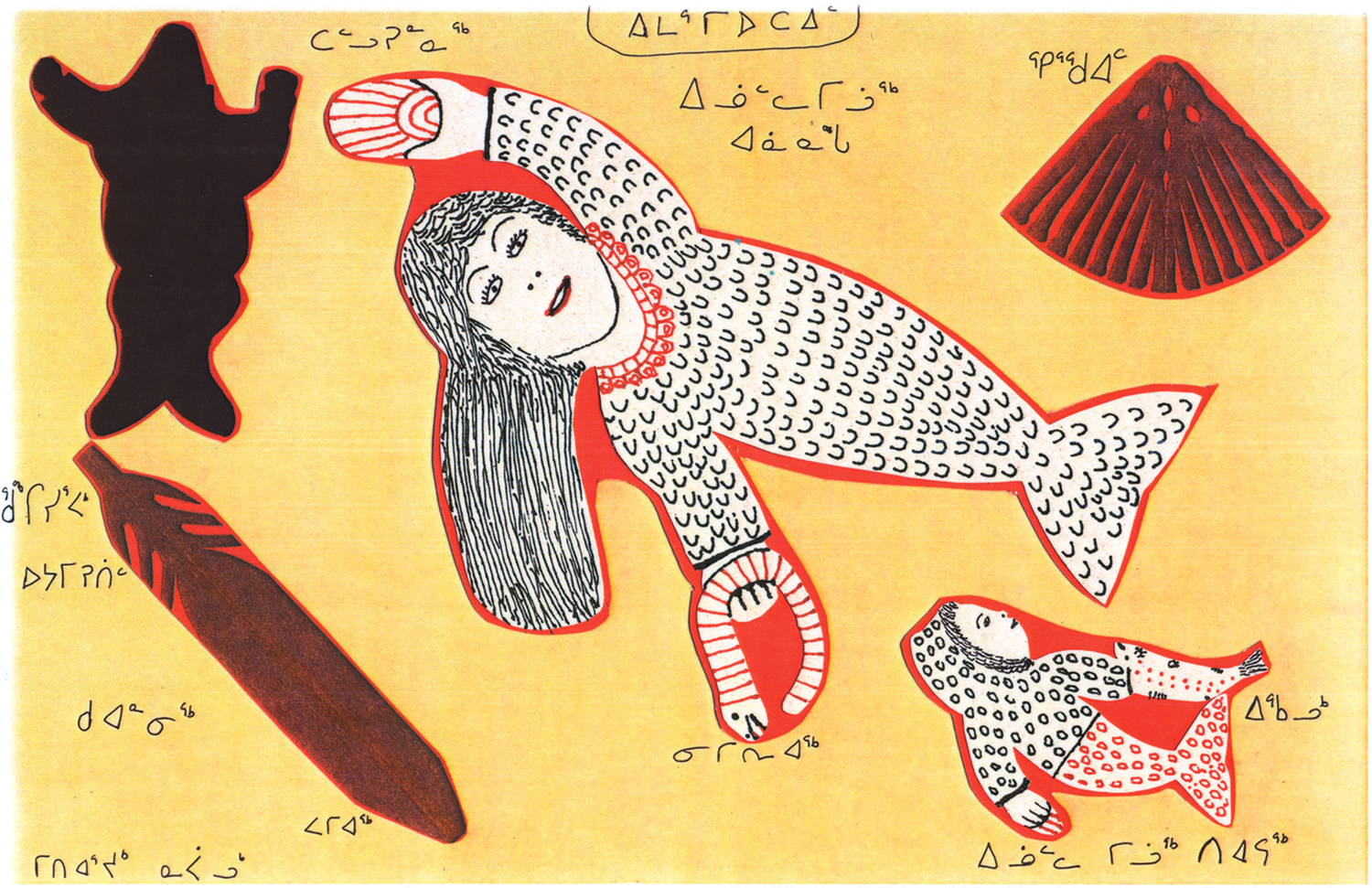

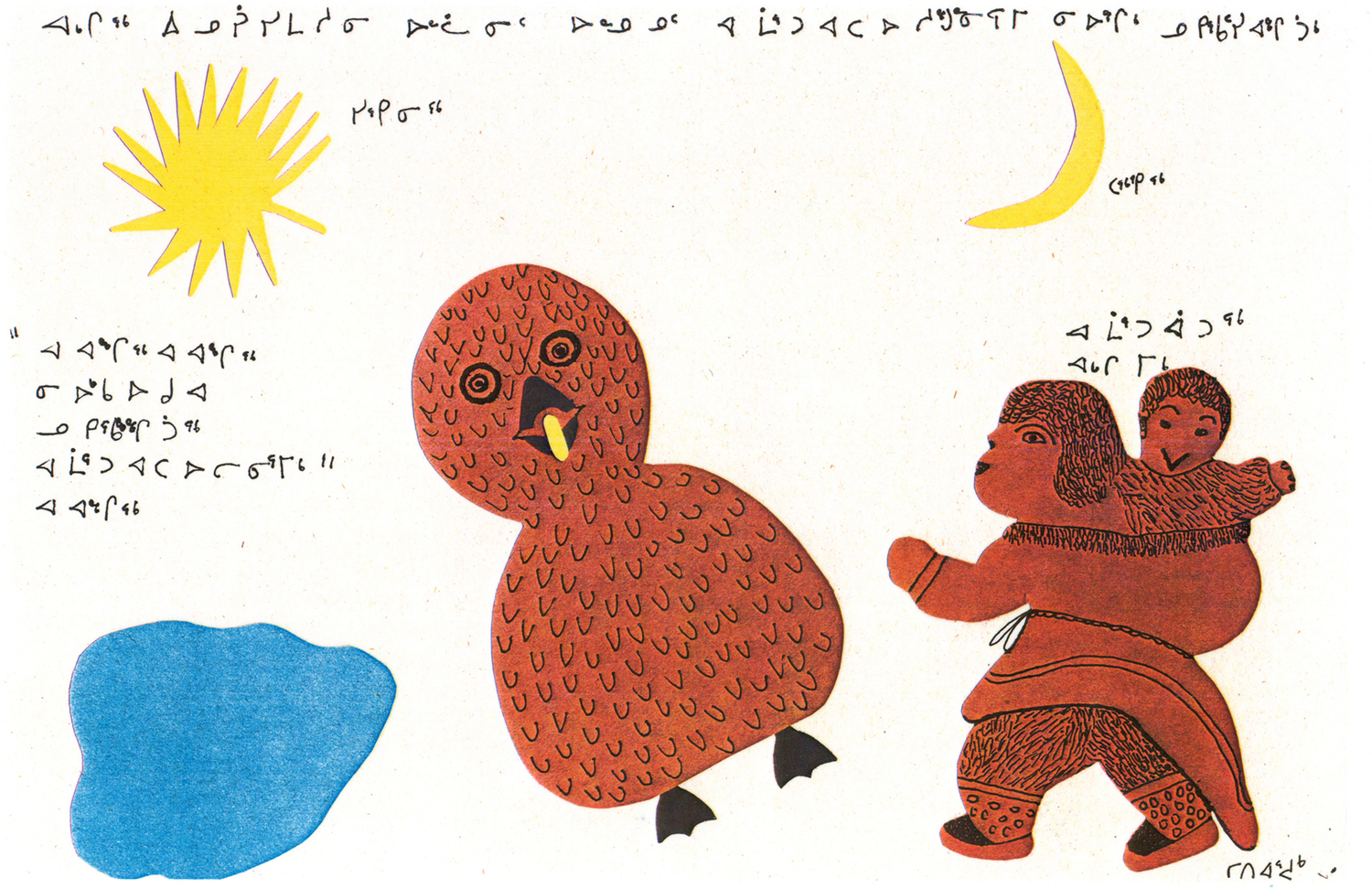

ᓯᕗᓪᓕᐹᑦᓯᐊᒍᑎᓗᒍ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᐅᓂᕐᐸᐅᓱᓂ, ᐊᓈᓇᒋᔭᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ 7-ᓄᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐊᕐᓇᕆᔭᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᐃᓚᒌᓄᑦ ᑐᑦᑕᕕᒋᔭᐅᑦᓱᑎᓗ ᖃᐅᔨᒪᓂᕐᓂᒃ ᑐᓴᐅᒪᑎᑦᓯᒋᐊᕐᓂᓂᒃ. ᐊᑖᑕᖓ ᐸᓂᖃᑐᐃᓐᓇᓂᕐᒪᑦ, ᐱᒍᓐᓇᓚᕿᑎᑦᓯᔪᕕᓂᖅ ᐊᖓᔪᑦᓯᐹᒥᓂᒃ, ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒥᒃ, ᐆᒪᔪᕐᓯᐅᓂᕐᒥᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᖃᓗᑦᓯᐅᓂᕐᒥᒃ, ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕐᑕᐅᕙᓪᓗᐸᑦᑐᕕᓂᐅᒐᓗᐊᕐᑎᓗᒋᑦ ᐱᐅᓯᑐᖃᕐᑎᒍᑦ ᐊᖑᑎᓄᑦ, ᐃᓚᒋᔭᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᐳᐃᒍᕐᓴᐅᖏᑦᑐᓄᑦ ᐆᒪᔪᕐᓯᐅᑎᓄᑦ. ᐊᓈᓇᒥᓄᓗ ᐊᓯᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᓕᓴᕐᑕᐅᕙᑦᑐᕕᓂᖅ ᐅᖃᐅᓯᑎᒍᑦ ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐱᓇᓱᐊᕆᐅᕐᑎᑕᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᐊᕐᓀᑦ ᑭᓯᐊᓂ ᐱᓇᓱᐊᓲᖏᓐᓂᒃ. ᑌᒣᒍᓐᓇᓂᕋᒥ ᐱᓗᐊᕐᑐᒥᒃ ᐃᓕᑕᕆᔭᐅᓗᐊᖕᖑᐊᓯᒪᔪᖅ ᓄᓇᓕᒥᓂ. ᐊᒻᒪᓗ, ᖃᐅᔨᒪᔭᐅᓪᓚᕆᑦᓯᒪᑦᓱᓂ ᐃᓂᕐᓯᓯᑎᐅᒋᐊᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᒥᓇᕐᑐᓕᐊᖏᑦ ᓴᓇᖕᖑᐊᑕᖏᑦ.

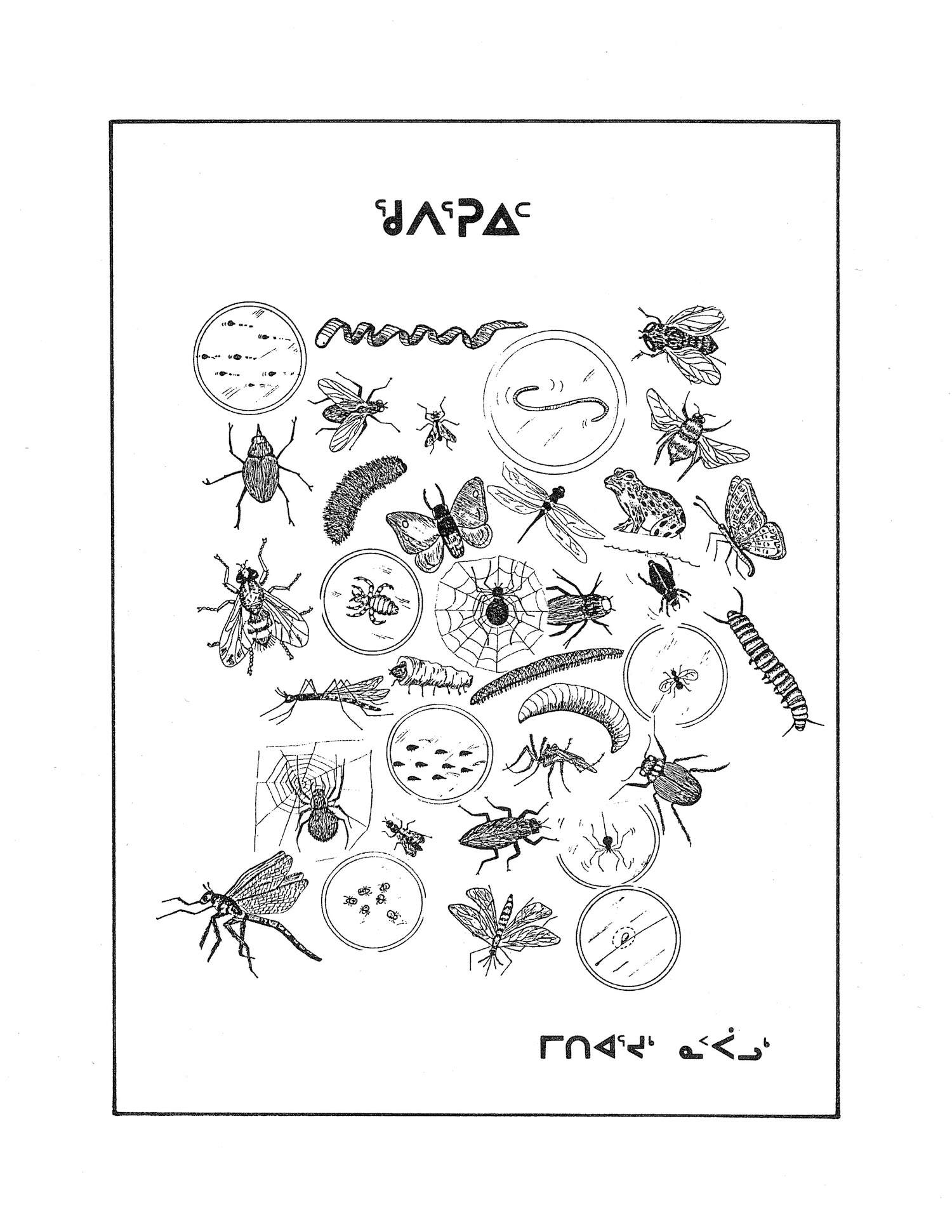

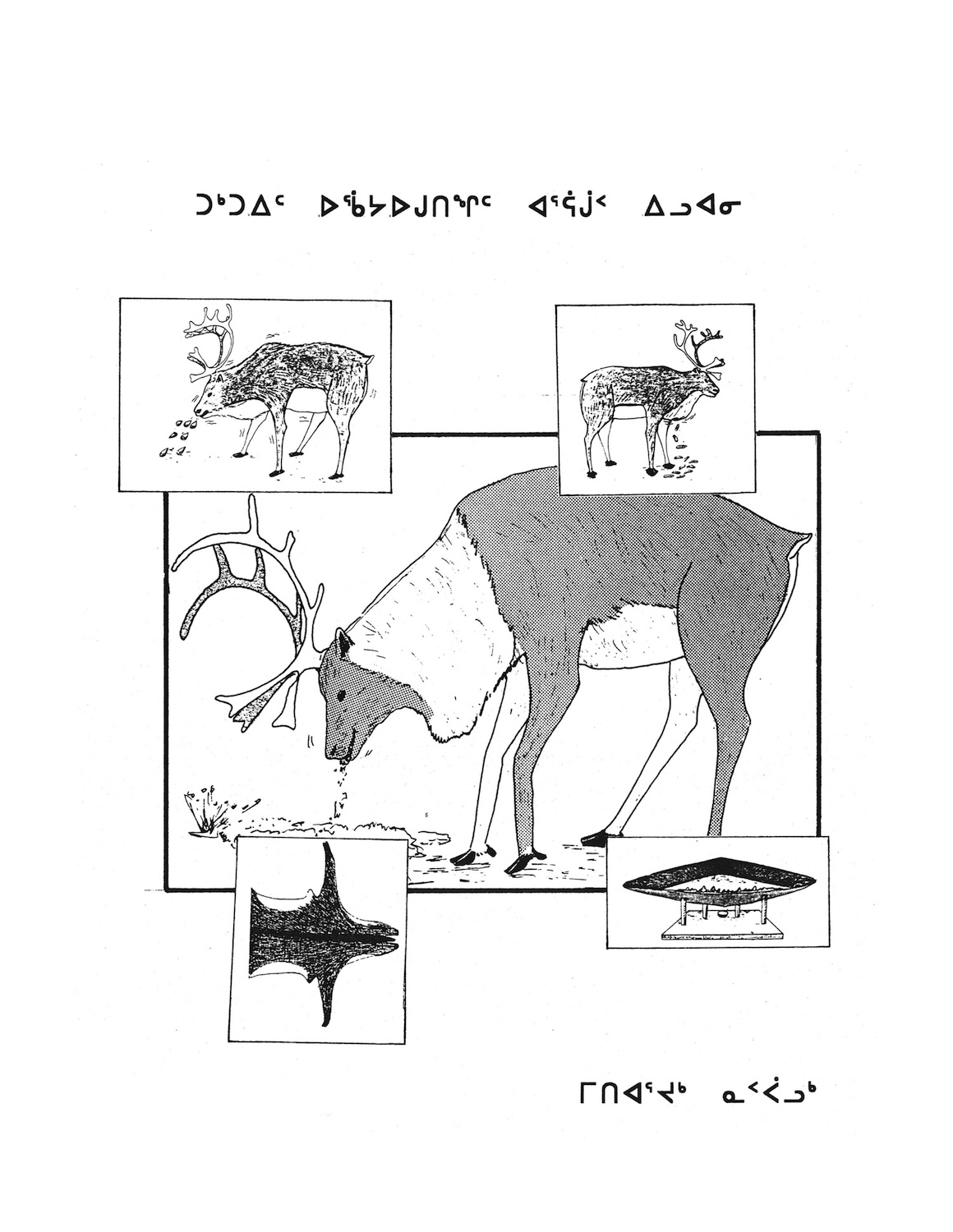

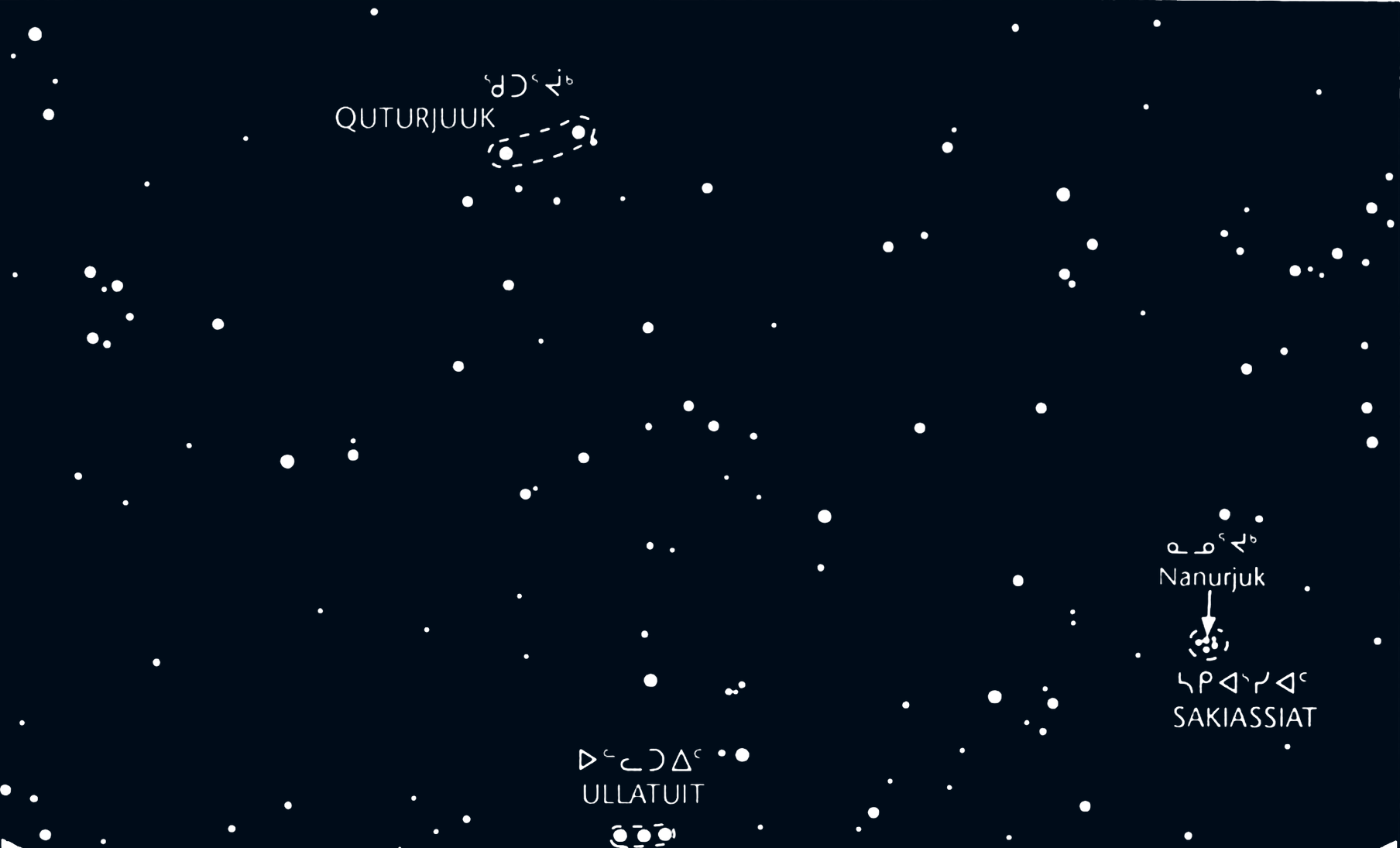

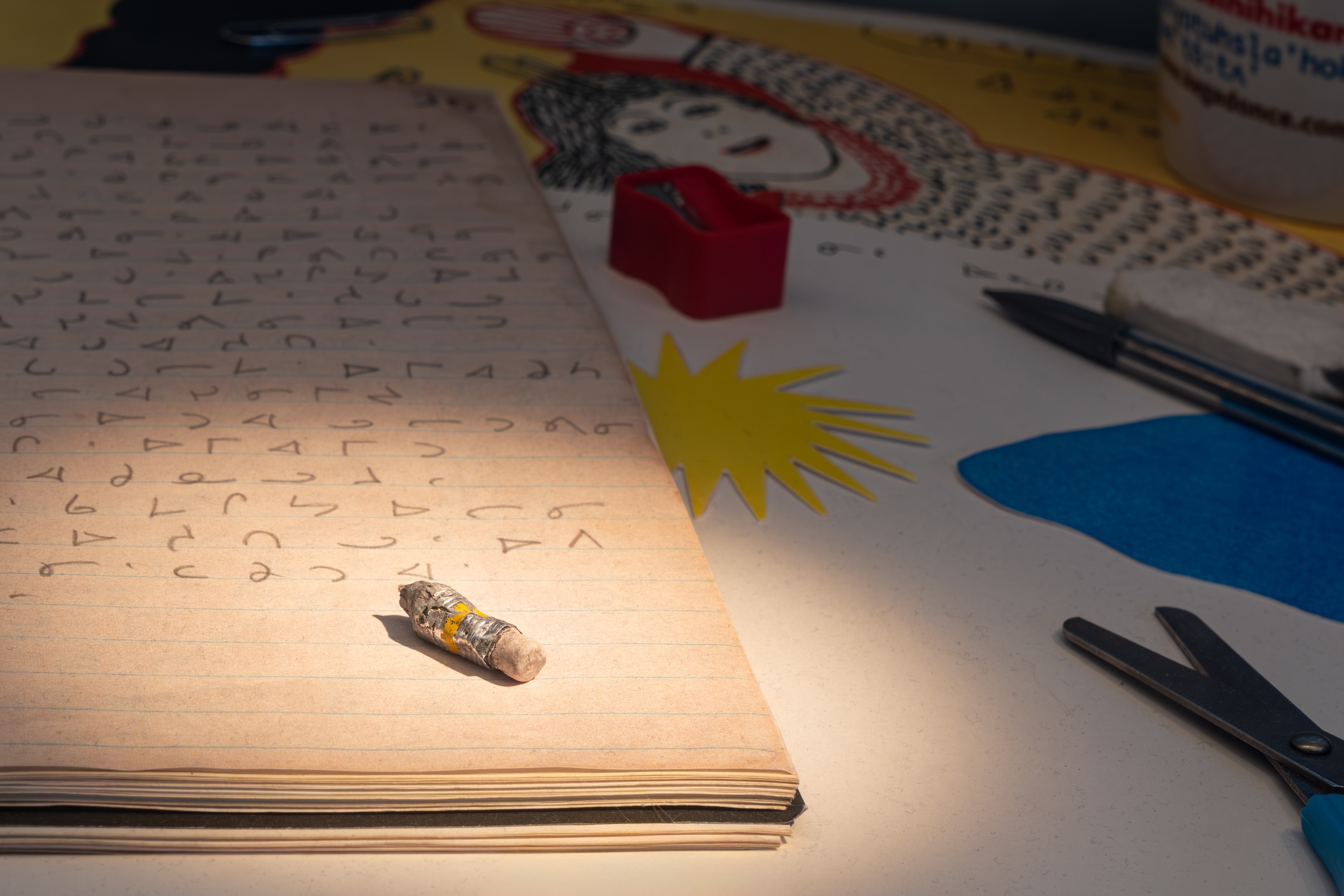

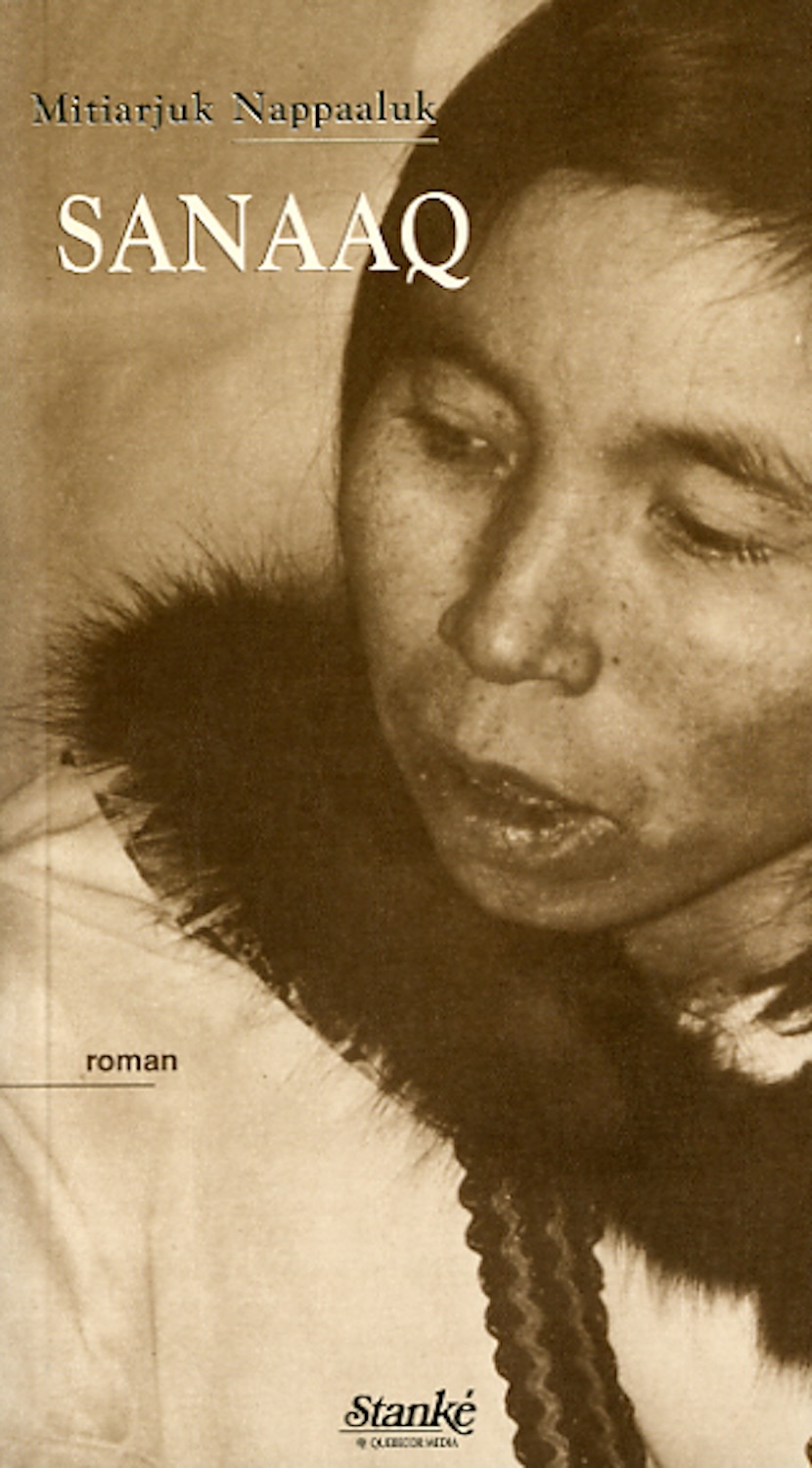

ᐊᔪᕿᕐᑐᐃᔩᑦ ᑎᑭᒻᒪᑕ, ᐃᓕᓴᕐᑕᐅᓱᓂ ᐃᕐᓯᕋᕐᔪᐊᑦ ᐊᔪᕿᕐᑐᐃᔨᖓᓄᑦ ᓕᓵᒧᑦ, ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑐᑦ ᐊᓪᓚᒋᐅᕐᑐᕕᓂᖅ. ᑖᓐᓇ ᓄᑖᒍᓕᕐᑎᓗᒍ ᐃᒻᒥᓂᒃ ᑐᓴᕐᑕᐅᑎᒍᓐᓇᓯᐅᑎᒋᒍᓐᓇᓕᕐᑕᕕᓂᖓ ᐊᓪᓚᒍᓐᓇᓯᑦᓱᓂ 20-ᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᐊᒐᕐᓂᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑐᓂᕐᕈᓯᕙᑦᓱᓂ ᕿᒥᕐᕈᖑᐊᓄᑦ ᐊᑐᐊᒐᕐᓄᑦ ᑐᒥᕗᑦ, ᐱᓯᒪᔪᓄᑦ ᐊᕙᑕᖅ ᐱᐅᓯᑐᖃᓕᕆᔨᒃᑯᓂᑦ. ᐊᖏᓂᕐᐸᐅᑎᓗᒍ ᐱᓚᕿᓯᒪᔭᖓ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᐸᐅᑦᔨᓱᒍ ᓴᓈᖅ, ᐱᒋᐊᕐᑕᕕᓂᖏᑦ 1950-ᒥ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑕᑯᔭᑦᓴᖑᕐᓱᑎᒃ 1983-ᒥ ᑖᒃᑯᐊᑕᒐ ᓯᕗᓪᓕᐸᐅᑦᓱᑎᒃ ᐊᑐᐊᒐᖕᖑᖄᕐᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑑᕐᓱᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑐᖓᓕᖏᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᑦᓴᖑᕐᑎᑕᐅᑦᓱᑎᒃ. ᐸᓂᖏᑦᑕ ᓄᑲᕐᓯᐹᖓ ᕿᐊᓪᓚᒃ ᐊᐅᓚᔨᔪᖅ ᒥᑭᔪᐊᐱᐅᖏᓐᓈᓱᓂ ᑕᑯᓐᓇᓱᓂ ᐊᓈᓇᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᓪᓚᑐᒥᒃ. « ᓴᓈᖅ ᐊᑐᐊᒉᑦ ᖃᓄᖅ ᑕᕐᕋᖅ ᐃᓅᕕᐅᒍᓐᓇᒪᖔᑦ, ᖃᓄᖅ ᐃᓄᐃᑦ ᐆᒪᒍᓐᓇᕕᖃᕐᓯᒪᒻᒪᖔᑕ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᖃᓄᖅ ᐃᓚᒌᑦᓯᐊᓲᒍᒻᒪᖔᑦ » ᓚᓚᐅᔫᖅ. ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᒃ ᕿᑐᕐᖓᒥᓂᒃ ᑌᒪᖕᖓᑦ ᐊᓪᓚᑕᕕᓂᕐᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᐊᕐᓯᕕᖃᕐᐸᑐᕕᓂᖅ ᐃᓄᓐᓄᑦ ᑕᑯᔭᑦᓴᖑᕐᑕᐅᓚᐅᕐᑎᓇᒋᑦ.

ᐅᖃᐅᓯᑐᖃᕐᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᕐᓱᓂ, ᐃᓄᑦᑎᑐᑦ, ᑖᒃᑯᐊ ᐊᑐᐊᒐᓕᐊᕕᓂᖏᑦ ᐊᒥᓱᐃᓂᒃ ᓵᓚᖃᐅᑎᑖᕈᑎᒋᓯᒪᔭᖏᑦ : ᑳᓇᑕᒥ ᓄᓇᖃᕐᖄᑐᕕᓃᑦ ᐱᓚᕿᓯᒪᔪᑦ ᐁᑦᑐᑕᐅᒍᑎᖓ 1999-ᒥ, Doctorat Honorifique de Université McGill 2000-ᒥ, Ordre du Canada 2004-ᒥ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ Mary Scorer ᐁᑦᑐᐃᒍᑎᖓ ᐱᐅᓂᕐᐹᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᐊᒐᓕᐅᕐᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ 2015-ᒥ.

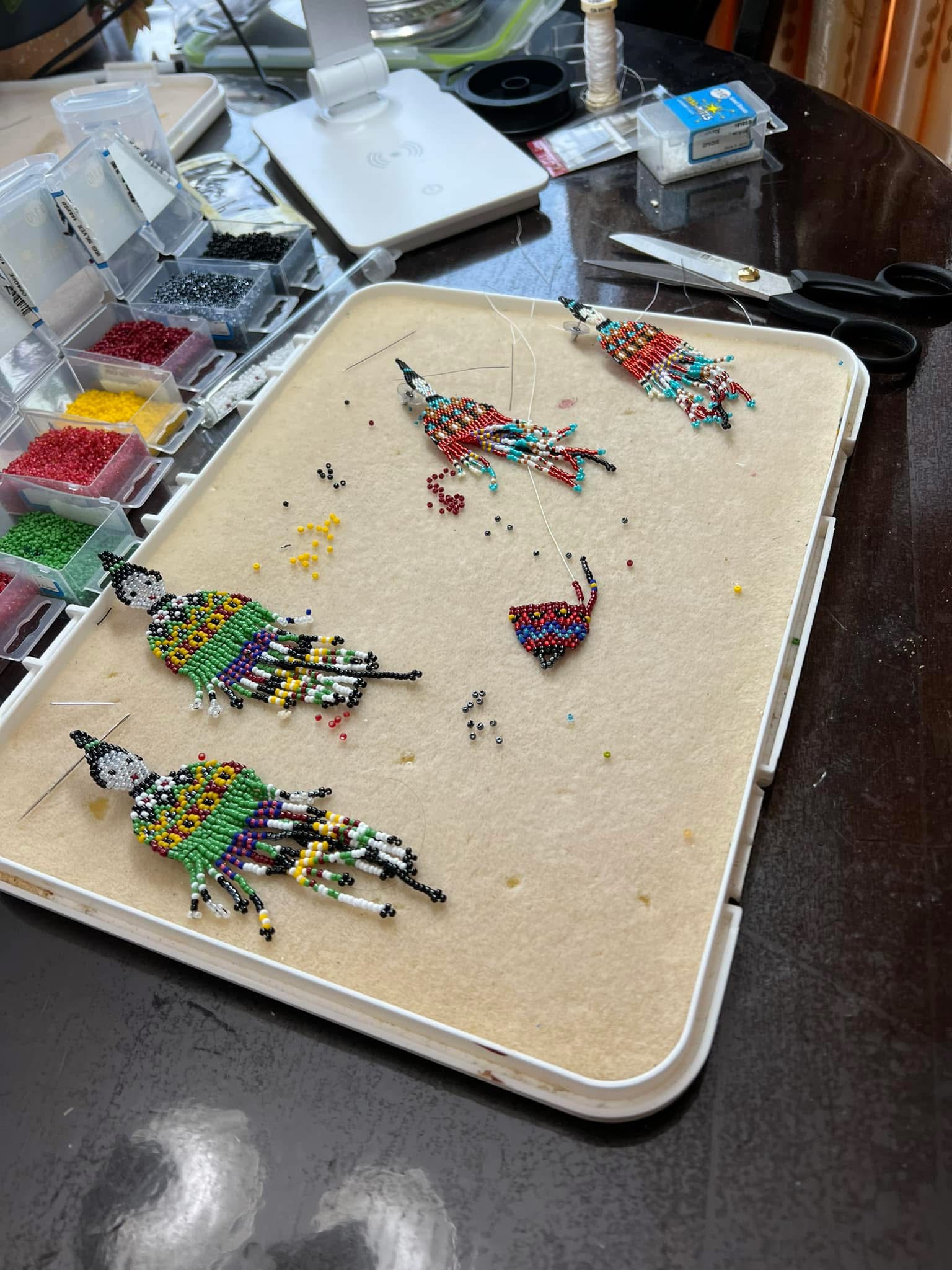

ᐃᕐᖃᐅᒪᔭᐅᒍᑎᖓᓂᒃ, ᓴᓈᖅ ᑲᑎᑦᑕᕕᐅᑉ ᐅᒃᑯᐊᖏᑦ ᐅᒃᑯᐃᑐᕕᓃᑦ ᔫᓂ 2025-ᒥ. ᑖᓐᓇ ᐃᓗᒡᒍᓯᓕᕆᕕᖓ ᒪᓐᑐᔨᐊᓪ ᓄᓇᕐᓚᖓᑕ, ᓇᔪᕐᑕᓂ ᐅᕙᓂ arrondissement Ville-Marie, ᐊᑐᐊᕐᓯᕕᐅᑦᓱᓂ, ᑕᑯᓐᓇᐅᔮᕐᑎᓯᕕᐅᑦᓱᓂ, ᕿᒥᕐᕈᕕᐅᑦᓱᓂ. ᓄᓇᓕᒥᐅᓂᓗ ᑭᒡᒐᑐᕐᕕᐅᓱᓂ ᓇᓗᓀᕐᑐᓯᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᖃᐅᔨᓴᕈᑎᓄᑦ, ᓂᐱᓕᐅᕐᕕᐅᓱᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᑎᒪᕕᐅᑦᓱᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑲᑎᒋᐊᓪᓚᕕᐅᑦᓱᓂ. ᕿᐊᓪᓚ ᑐᑭᓯᑎᑦᓯᓚᐅᕐᑐᖅ: “ᐊᓈᓇᒐ ᐃᓱᒪᑕᒻᒪᕆᐅᓯᒪᔪᖅ, ᐅᓂᒃᑳᓯᑎᐅᑦᓱᓂ, ᓇᓪᓕᒍᓱᑦᓱᓂ, ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓕᓭᔨᑦᓯᐊᒪᕆᐅᑦᓱᓂ. ᑕᒫᓃᖏᓐᓈᑐᕕᓂᐅᒍᓂ ᐊᓕᐊᒐᓱᐊᒻᒪᕆᒐᔭᕐᑐᖅ.” ᓄᓇᕐᓚᖅ ᑕᑯᕐᖃᔭᕐᓯᒪᖕᖏᑐᖅ ᐱᐅᓂᕐᓴᒥᒃ ᐃᕐᖃᐅᒪᑎᑦᓯᐅᑎᑦᓴᒥᒃ ᐃᓕᓴᕐᕕᐅᒍᓐᓇᓱᓂ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᓂᕐᓯᕕᐅᒍᓐᓇᓱᓂ. ᓴᓈᖅ ᑲᑎᑦᑕᕕᒃ ᐅᒃᑯᐃᓂᖃᕐᑎᓗᒍ ᓇᑉᐹᓗᒃᑯᑦ ᐃᓚᒌᑦ ᐁᓯᒪᓚᐅᔫᑦ ᒣ 7-ᐅᓚᐅᔫᒥ, ᐃᓗᓕᓕᒃ ᓴᓇᕐᕙᓯᒪᕕᓐᓂᒃ ᐃᕐᖃᐅᒪᔭᐅᒍᑎᒋᔭᖏᓐᓂ ᕿᒻᒪᑯᒍᑎᒋᓯᒪᔭᖏᓐᓂᒃ ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔫᑉ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᑭᓇᓕᒫᒃᑯᓄᑦ ᐱᕕᑦᓴᐅᒍᓐᓇᓱᓂ ᖃᐅᔨᒋᐊᕈᒪᔪᓂᒃ ᐱᒻᒪᕆᓐᓂᒃ ᑐᓂᕐᕈᓯᒍᑎᒋᓯᒪᔭᖏᓐᓂᒃ. ᐱᓇᓱᒐᖅ ᓴᐳᑦᔭᐅᔪᖅ ᐊᕙᑕᒃᑯᓄᑦ ᐊᑦᔨᒌᖕᖏᑐᓄᑦ ᑕᑯᒥᓇᕐᑐᓕᐅᕐᑎᓄᑦ ᑐᓂᕐᕈᓯᕕᐅᓯᒪᑦᓱᓂ ᐆᑦᑑᑎᒋᑦᓱᒋᑦ ᓘᑲᓯ ᑭᐊᑌᓐᓇᖅ, ᑑᒪᓯ ᒪᖏᐅᖅ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᔮᓂᔅ ᑯᔩ.

ᕿᐊᓪᓚᖅ ᓂᕆᐅᑦᓯᐊᑐᖅ ᓯᕗᓂᕐᒥ ᐃᓅᖃᑦᑕᓛᕐᑐᑦ ᐃᓕᑦᓯᕕᒋᖃᑦᑕᓛᕐᑕᖓᓂᒃ ᐱᕙᓪᓕᐊᒍᑎᒋᓯᒪᔭᑦᑎᓂᒃ, ᐃᓗᓯᕐᓱᓯᐊᕐᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᐃᑲᔪᕐᑎᒌᑦᓯᐊᓗᑎᒃ ᐊᓯᒥᓂᓗ ᐃᑲᔪᕐᑎᐅᓗᑎᒃ, ᒥᑎᐊᕐᔪᑎᑐᑦ ᐊᒻᒪᓗ ᓄᓇᓕᒋᓚᐅᔪᔭᖓᑎᑐᑦ. “ᐊᓈᓇᒐ ᓚᕙᓚᐅᕐᑐᖅ: ᐃᓕᑦᓕᓯᖃᑦᑕᕆᐊᖃᕐᑐᒍᑦ ᐊᑕᐅᓯᕐᒥᐅᓃᑦ ᐅᓪᓗᑕᒫᑦ, ᑖᓐᓇ ᓈᒻᒪᑐᖅ.”

Mitiarjuk Attasie Nappaaluk, originaire de Kangiqsujuaq, était dotée de grandes connaissances, et d’une ferveur et d’une passion pour la transmission de sa culture. Décédée en 2007, Mitiarjuk a laissé derrière elle une panoplie d’histoires et de souvenirs pour les générations à venir. De 1965 jusqu’en 1996, elle a pu travailler pour Kativik Ilisarniliriniq en tant que consultante et enseignante d’inuktitut et de culture dans les écoles du Nunavik.

Avant tout, c’était la mère de sept enfants et une femme pour qui la famille était au centre du partage des connaissances. Puisque son père n’avait que des filles, il a transmis à son aînée, Mitiarjuk, les pratiques de la chasse et de la pêche, des activités traditionnellement plus masculines, ainsi que les légendes de la chasse. Sa mère, quant à elle, lui a appris les récits oraux et les activités réservées aux femmes. Cette particularité lui a procuré une reconnaissance dans sa communauté. En plus de cela, elle était reconnue pour sa créativité et son art.

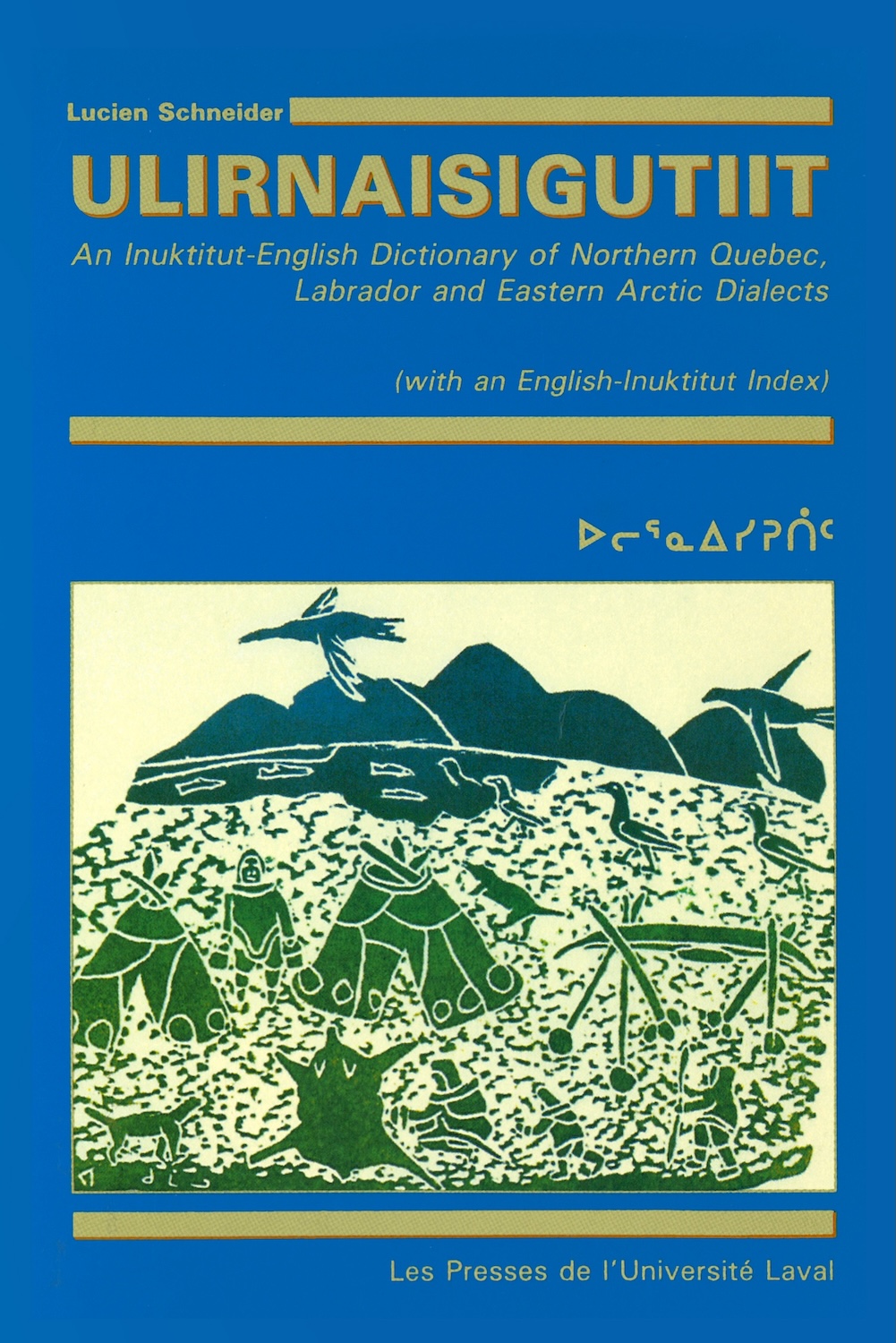

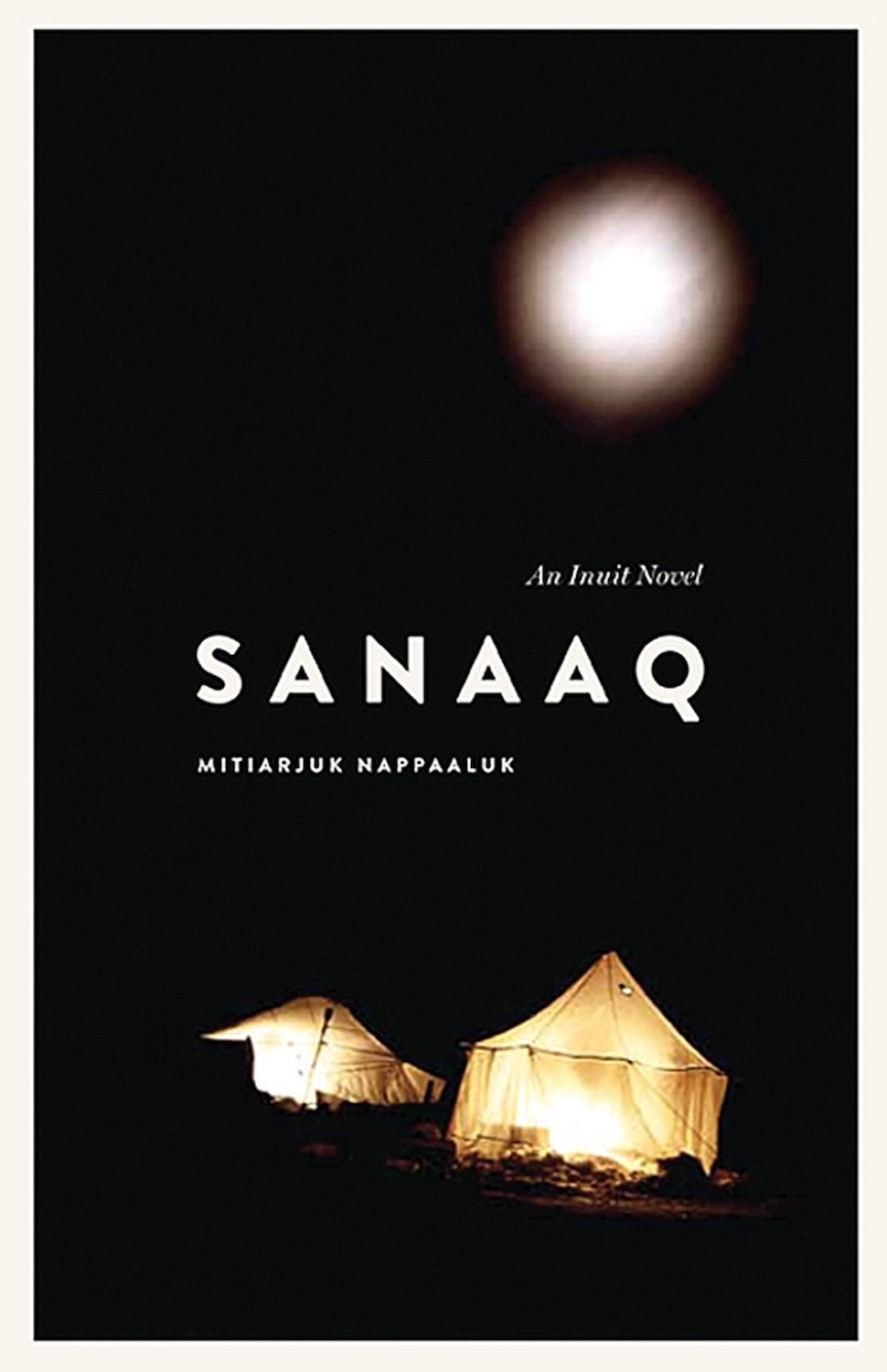

À l’arrivée des missionnaires, avec le père Lechat, elle apprit à écrire le syllabique. Cette nouvelle manière de s’exprimer lui a permis d’écrire une vingtaine de livres et de contribuer au magazine Tumivut, de l’Institut culturel Avataq. Son plus grand succès et son premier livre est Sanaaq, commencé en 1950 et publié en 1983, ce qui en fait le premier roman écrit en inuktitut et le second publié. Sa fille cadette, Qiallak, se souvient depuis son plus jeune âge de la voir écrire. « Sanaaq est un livre qui porte sur comment vivre dans le nord, comment les Inuit survivaient et comment être une famille » dit-elle. Mitiarjuk lisait toujours ses livres à ses enfants avant de les partager avec le public.

Écrit dans sa langue maternelle, l’inuktitut, ce livre a remporté de nombreux prix : National Aboriginal Achievement Award en 1999, Doctorat Honorifique de Université McGill en 2000, Ordre du Canada en 2004 et Mary Scorer Award for Best Book en 2015.

En son hommage, le Centre Sanaaq a ouvert ses portes en juin 2025. Ce centre culturel de la ville de Montréal situé dans l’arrondissement Ville-Marie est une bibliothèque, une salle de spectacle, une galerie et des services aux citoyens comme un laboratoire numérique, des studios d’enregistrement et des lieux de rencontre et d’évènements. Qiallak explique : « Ma mère était très intelligente, bonne conteuse, aimante, et éduquait merveilleusement bien. Si elle était encore là, elle serait très heureuse. » La ville n’aurait pas pu trouver meilleur hommage pour un lieux d’apprentissage et de création. Le Centre Sanaaq, dont l’ouverture officielle en présence de la famille Nappaaluk a eu lieu le 7 mai dernier, contient une vitrine muséale permanente qui honore l’héritage de Mitiarjuk et permet au public de découvrir son importante contribution. Un projet porté par Avataq et auquel plusieurs artistes ont contribué dont Lucasi Kiatainaq, Thomassie Mangiok et Janice Grey.

Qiallak espère que les générations futures pourront s’éduquer sur notre histoire, qu’ils soient en santé et s’entraident, comme Mitiarjuk et sa communauté le faisaient. « Ma mère disait : Il faut au moins apprendre une chose par jour, c’est assez. »

Mitiarjuk Attasie Nappaaluk, originally from Kangiqsujuaq, was endowed with good amount of knowledge, fervor and passion for the transmission of her culture. Passed away in 2007, Mitiarjuk left behind her panoply of stories and memories for the generations to come. From 1965 to 1996, she was able to work for Kativik Ilisarniliriniq as consultant and teacher in Inuktitut and of the culture in the schools of Nunavik.

Before all, she was a mother of seven children and a woman for which the family was the center of sharing knowledge. Since her father only had girls, he transmitted to her eldest, Mitiarjuk, the practices of hunting and fishing, activities traditionally more masculine, and hunting legends. Her mother, on the other hand, taught her oral history and other woman’s activities. This particularity gave her recognition in her community. In addition, she was recognized for her creativity and her art.

At the arrival of the missionaries, with Father Lechat, she learned to write syllabic. This new way to express herself allowed her to write about twenty books and to contribute to the Tumivut Magazine, from the Avataq Cultural Institute. Her biggest success and her first book is Sanaaq, started in 1950 and published 1983, which makes it the first novel written in Inuktitut and the second published. Her youngest daughter, Qiallak, remembers since her young age to see her write. “Sanaaq is a book about how to live in the north, how the Inuit survived and how to be a family” she says. Mitiarjuk always read her books to her children before publishing them to the public.

Written in her mother tongue, Inuktitut, this book won numerous prizes: National Aboriginal Achievement Award in 1999, Honorary Doctorate of McGill University in 2000, Order of Canada in 2004 and Mary Scorer Award for Best Book in 2015.

As a tribute for her, the Sanaaq Center opened its doors in June 2025. This cultural center of the City of Montreal, located in the borough of Ville-Marie, is a library, concert hall, a gallery and provides citizen services such as numeric labotary, recording studios and a place of gathering and events. Qiallak explains: “My mother was very smart, good storyteller, loving, and taught beautifully well. If she was still here, she would have been very happy.” The city couldn’t have found a better tribute for a learning space and creation. The Sanaaq Center which opened officially in presence of the Nappaaluk family happened on May 7th, contains a permanent museal showcase that honors the heritage of Mitiarjuk and allows the public to discover her important contribution. A project run by Avataq and which multiple artists contributed such as Lucasi Kiatainaq, Thomassie Mangiok and Janice Grey.

Qiallak hopes the future generations will learn on our history, to be healthy and help one and other, like Mitiarjuk and her community did. “My mother always said: We need to at least learn one thing every day, it’s enough.”

ᐊᓪᓚᑐᖅ | Texte de | Text by: Jessie Fortier-Ningiuruvik

ᐊᑦᔨᓕᐊᕕᓂᕐᒥᓂᒃ ᐊᑐᕐᑕᐅᑎᑦᓯᓯᒪᔪᑦ / Crédits photos / Photos credits[display credits]: Marie-Christine Couture – Institut culturel Avataq